Sure, the long wait for the Tesla Model 3 may extend into 2019. And sure, electric vehicles may be the future. But despite growing interest today, the concept of electric vehicles is just a resuscitation of a long-dormant method of commuting—one that first materialized in the 1800s.

Happy Sunday! Welcome to Holy Shift, where we highlight big innovations in the auto and racing industries each week—whether they be necessary or simply for comfort.

If there ever was a perfect application for the phase “ahead of its time,” the idea of an electric car is probably it. That’s not to say the cars weren’t popular 100 years ago—in fact, the U.S. Department of Energy cites electric cars as making up about a third of all vehicles on the road in 1900. In 1911, the New York Times even called existing electric vehicles “ideal.”

Advertisement

But, by 1935, electric cars were nearly nonexistent. It took decades for that to change.

Let’s start at the beginning. Attempts at electric vehicles came as early as the 1830s, with some of them being successful—according toPBS, the first practical electric vehicle was a small locomotive built by American Thomas Davenport in 1835.

Sponsored

As for full-size automobiles, the first practical one in the U.S. came by the hands of William Morrison in 1890. The Department of Energy describes it more as an “electric wagon,” able to hold six people and with a top speed of 14 mph.

Automakers got in on the electric trends soon after. The Pope Manufacturing Company of Connecticut became the first large-scale manufacturer of electric automobiles in 1897, per PBS, and Thomas Edison even began a project to create a more powerful and longer lasting battery for electric cars within the next two years. Edison eventually gave up on the project a decade later, according to PBS.

In 1898, engineer Ferdinand Porsche joined the electric market. Decades before the founding of the automaker with his namesake in 1931, Porsche developed an electric vehicle known as the “Lohner Porsche.” He also came out with a hybrid concept in 1900, combining his electric setup with a combustion engine and calling it the “Semper Vivus.”

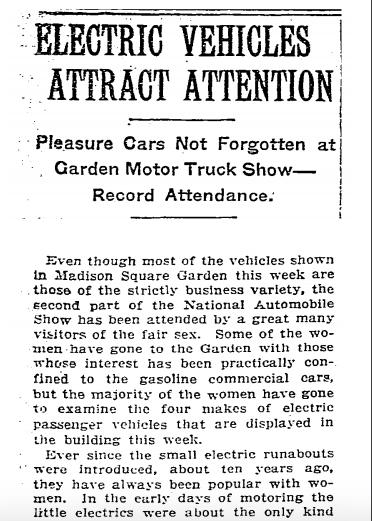

To underscore the popularity of electric transportation at the time, there also happened to be a fleet of more than 60 electric taxis in New York City around the turn of the 20th century. A 1911 New York Times article described how electric cars were popular among women in particular, because “early gasoline cars required more strength to crank than most women possess.” (Thank goodness we as a society have evolved in more than just the automotive industry, right?)

Advertisement

But the first decade of the 1900s was the peak of electric cars—at least, for a long time to come. Henry Ford introduced the concept of mass production of cars onto the market, drastically reducing the price of gasoline-powered vehicles by around 1912. For comparison, a gasoline car during that year cost $650, while an electric roadster sold for nearly three times the price at $1,750.

Car price alone wasn’t the only factor contributing to the original demise of the electric vehicle, though. From the U.S. Department of Energy’s website:

By the 1920s, the U.S. had a better system of roads connecting cities, and Americans wanted to get out and explore. With the discovery of Texas crude oil, gas became cheap and readily available for rural Americans, and filling stations began popping up across the country. In comparison, very few Americans outside of cities had electricity at that time.

The electric car had its advantages, despite all of the factors working against its success—according to Tech Insider, gasoline- and steam-powered cars produced much more noxious smells, vibrations and road noise. In addition, the electric cars were easier to operate than gasoline cars and had a longer range than those powered by steam.

But in the end, electricity lost out to affordability and simplicity. The era of the electric car ended, with the 1930s onward seeing fewer and fewer on the road.

http://jalopnik.com/5870808/how-a-…

An attempt came in 1959 to bring the electric vehicle back onto the scene, when the Henney Kilowatt came about. Per Business Insider, the 1959 model could run 40 miles on a charge and had a top speed of 40 mph. Those numbers both rose to 60 for the 1960 model of the car, but it just wasn’t enough—of the 100 total Kilowatts produced during its two years in production, only 47 sold.

But the idea never died out completely. According to PBS, the U.S. Congress introduced early bills in 1966 that recommended using electric cars as a method to reduce air pollution. At the time of the bills, a Gallop poll found 33 million Americans to be interested in electric vehicles.

According to the Department of Energy, rising gas prices and more frequent shortages led to a movement concerned with lowering U.S. dependence on oil from foreign countries and finding more domestic fuel sources. Electric cars began to rise again, but more in the realm of interest rather than practicality. Most, at the time, had a range of around 40 miles and speeds typically topped off at 45 mph.

As the interest in electric cars remained just that—an interest—about 20 years passed. The late 1990s were when the current push for electric vehicles entered the scene, with the first mass-produced hybrid electric car, the Toyota Prius, coming on the market in Japan in 1997. The Prius went global in 2000.

Tesla Motors came around just a few years later in 2006, and the market for electric cars is so large now that giving them all a mention would likely drive you to stop reading from fatigue.

But despite the advances of electric cars and the designs now in the works that will feature logos from the likes of Porsche, Bentley, Audi and others, electric cars still only make up a small percentage of those on the road. There’s still room for the industry to grow, but with 253,000 Tesla Model 3 orders in the two days after its debut, the future looks bright—although lately, super-cheap gas prices have put a huge damper on hybrid and EV sales compared to years past. Industry observers worry that trend could stunt EV development yet again.

Whether we’re in for another demise of the electric car remains to be seen, but it looks as if the era of charging cars is here for the long run this time around.

If you have suggestions for future innovations to be featured on Holy Shift—in street cars, the racing industry or whatever you’d like—feel free to send an email to the address below or leave them in the comments section. The topic range is broad, so don’t hesitate with your ideas.