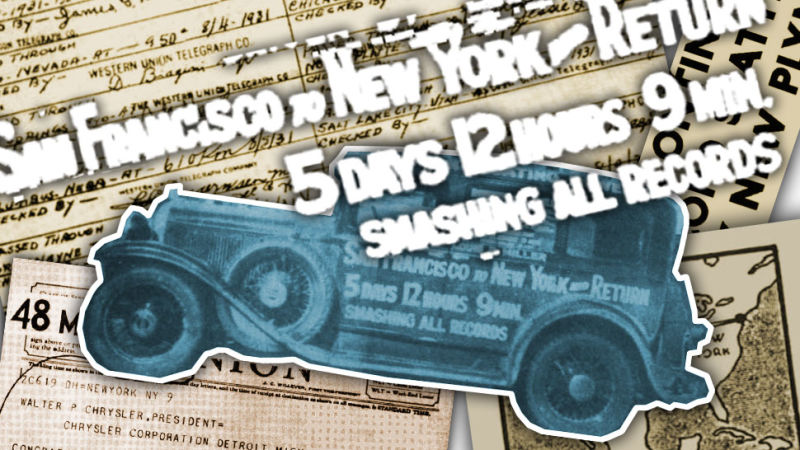

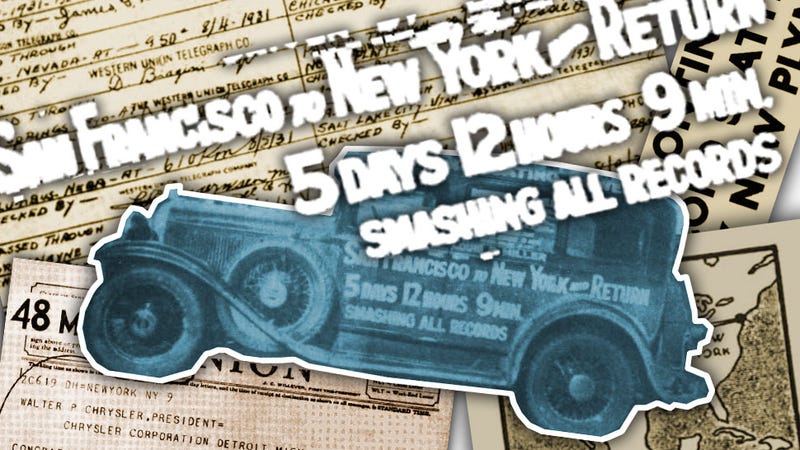

Ed Bolian may have been able to cross the country in just 28 hours and 50 minutes in a modified Mercedes CL55 AMG and modern highways, but in 1931, things were a lot more difficult. Here’s the story, courtesy of The Plymouth Bulletin, of the men who did it first, one of whom was Earl Pribek, uncle to John Z. DeLorean. — Ed.

On a warm day in late July of 1931, two men stood near the end of the assembly line of the new Plymouth plant in Detroit and watched the shiny new PA’s rolling off the line. The plant — boasting the longest automotive assembly line in the world — had been built in 1929 to meet the ever-increasing demand for the new Plymouth automobile now in its fourth model year of production. The two men were Earl Pribak, 23, a driver-mechanic employed at Chrysler’s Central Engineering facilities in Highland Parle, and Lou Miller, 57, West Coast Regional Sales Manager for Dodge Division of Chrysler Corporation.

As the men watched, Harry Heath, Plymouth Sales Representative, selected one of the new PA’s at random as it rolled off the end of the line. The car selected was a dark blue, 4-door, 6-wheel sedan, with trunk rack. Earl and Lou then drove the car, without further preparation, directly to San Francisco, following Route 30 to Salt Lake City and then Route 40 into San Francisco.

Advertisement

Advertisement

On the way to San Francisco, they stopped at each town of any consequence to check out the location of the local Plymouth dealer. The trip to San Francisco went smoothly, with the exception of an unscheduled detour into a farmer’s barnyard when Earl missed a sharp turn in Route 30 near Grantsville, Utah. Earl recalls that he took quite a bit of kidding at the time from Lou about this barnyard detour.

The car arrived in San Francisco in the last week of July and was driven directly to a local Plymouth dealership where several modifications were performed. The rear seats and rear interior trim were torn out and a 100-gallon galvanized steel tank, fabricated at a local job shop, was fitted into the rear passenger compartment. The tank was rectangular with a six-inch diameter circular opening at the top capable of receiving three or four gasoline hoses at a time. A hole was cut in the rear floor behind the 100-gallon tank and a feed pipe was run from the bottom of the tank through the hole in the rear floor and into the top of the standard 12-gallon tank. A hand valve was fitted into the feed pipe to allow gasoline to be selectively drained from the 100-gallon tank into the standard tank. Control of the valve was by a valve handle positioned above and to the rear of the 100-gallon tank.

Their attempt must have seemed a little brash, if not foolhardy.

Two road lights, mounted to turn with the front wheels, were installed on a bar mounted above the front bumper and a large Klaxon horn. operated by a button on the inside of the left front door, was mounted on top of the left front spare tire.

Sponsored

The standard trunk rack was removed and replaced with a spare tire carrier and a third spare tire, complete with chains, was mounted on the carrier. The car was now ready.

At exactly 5:00 a.m. on August 4, 1931, Earl and Lou wheeled the PA away from the Berkeley Pier in San Francisco and headed East toward New York City in an attempt to set a new trans- continental record for the round trip run from San Francisco to New York and return.

Advertisement

Their attempt must have seemed a little brash, if not foolhardy, to some since their vehicle — at 4 cylinders, 56 H.P., 109-inch wheelbase, 2,900 lbs., and $635 FOB — was rather puny and insignificant when compared to the reigning record holder, a 1930 air-cooled Franklin driven by Cannonball Baker and weighing in at 6 cylinders, 95 H.P., 125-inch wheelbase, 4,000 lbs., and $2,500 FOB.

Earl and Lou drove the PA through the city streets of greater San Francisco at as fast a speed as traffic and road conditions would allow and then, once clear of the city, floored the PA for the long climb on U.S. Route 40 up the western slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Sacramento, Roseville, Auburn, Emigrant Gap, and Truckee all passed in a blur as they streaked across California. Somewhere during this race across California, they performed a ritual that was to be repeated regularly every 150 miles or so for the next several days. As the needle of the gasoline gauge on the instrument panel dropped toward the empty mark, the relief driver reached back over the 100-gallon gas tank and turned the valve handle to allow gasoline to flow from the 100-gallon tank into the standard 12-gallon tank. As soon as the needle on the gas gauge reached the full mark the hand valve was closed.

Advertisement

Earl and Lou completed the trip across California without incident and roared into Reno. Nevada, at 9:50 a.m. In Reno, they drove directly to the local Western Union Office where their time of arrival was verified. They then continued on at top speed on Route 40 across the hot hilly terrain of northern Nevada. While traveling across Nevada they performed a second ritual that like the gasoline tank filling routine was to be repeated several times in the next several days. While Lou slowed the PA from its top speed (with the added load of the gasoline tank, etc.) of 62 mph to 40 mph, Earl, carrying a couple of opened oil cans, climbed out onto the right front fender. opened the right side hood, reached across the engine to remove the oil filler cap, and poured the contents of the cans into the crank case.

As the shadows lengthened and the hot daytime sun gradually gave way 10 the cooler evening air, they reached the western border of Nevada and stormed into Utah. As darkness fell, they flicked on the two headlights and two running lights to illuminate Route 40 as it lay in front of them in a long straight ribbon of concrete stretching across the Great Salt Lake Desert toward Salt Lake City. They sped into Salt Lake City several hours later as midnight of their first day approached. Here they stopped at the first of four servicing points that had been set up by Chrysler at large gasoline stations located at spaced intervals across the United States.

Advertisement

As the PA screeched to a stop at the servicing point, four gasoline hoses were inserted simultaneously into the large opening in the 100-gallon gasoline tank, the oil level was checked, the tires and wheels checked, and the men given boxed chicken lunches. In a few minutes they were on their way again, gas pedal again pressed firmly to the floor, four headlights again steadily piercing the early morning darkness.

A few miles out of Salt Lake City they left Route 40 and picked up U.S. Route 30 for the long uphill climb to Rock Springs, Wyoming. the second Western Union check point. The road between Salt Lake City and Rock Springs was extremely rough and dotted with exasperating time-consuming detours. The road was so bad in spots that one of the wheels became bent from the continual pounding of the tires over the potholed pavement, allowing the tube to slip out from between the tire and rim and causing a blowout. Earl and Lou quickly stopped the car and changed the bent wheel in the early Wyoming morning darkness.

By now the rain had stopped and the roads were again paved.

They arrived at the Rock Springs. Wyoming check point at 3:00 a.m. on the 5th of August, sped through the dark, deserted streets to the local Western Union Office where their arrival time was verified and then picked up Route 30 again for the long uphill climb to the peak of the Continental Divide some 80 miles to the east. They reached the divide as daylight broke on the second day of their journey and continued on across Wyoming at top speed passing successively through Rawlins, Laramie, and Cheyenne, and finally reaching and crossing the Nebraska border as the noon hour of their second day approached.

Advertisement

The road which up to now had been mostly paved now turned to dirt and crushed rock and the weather, which up to now had been fair, now turned to rain. Earl and Lou continued on at top speed through the rain and mud, arriving at their second servicing point in North Platte, Nebraska the early afternoon of August 5. At North Platte, in addition to refueling and other servicing, they picked up a new tire and wheel to replace the bent one that they had changed between Salt take City and Rock Springs.

From North Platte, they pushed on through the continuing rain towards their third Western Union check point at Columbus, Nebraska. They reached Columbus at 6:10 p.m., checked in with the local Western Union Office. and set out on the long leg to their third servicing point al Aurora, Ilinois.

Advertisement

By now the rain had stopped and the roads were again paved. They crossed the remaining section of Nebraska in the early evening hours of August 5, rushed Into Iowa as darkness began to fall on the second day of their journey, sped across Iowa in the late evening of August 5 and thundered into Illinois in the early morning hours of August 6.

Shortly before reaching the Aurora servicing point they were arrested by an Ilinois State Trooper for speeding – 62 mph in a 50 mph zone. Acting in accordance with the prearranged plan in such an event, they paid the $20 fine on the spot and without complaint. In the darkness of the early morning hours, the arresting officer failed to notice the gigantic gas tank hulking in the rear seat, or the four beams of the multiple headlights piercing the dark night air. After allowing the unsuspecting officer to drive out of sight. Earl and Lou resumed their breakneck plunge across Illinois toward the Aurora service point.

They reached the Aurora service point without further incident and after a brief stop for the usual servicing and food, continued on Route 30 toward the fourth Western Union check point at Fort Wayne, Indiana. Just outside of Aurora. their first serious trouble developed. At about 3:00 a.m., with Lou driving, the generator bracket broke and the generator belt new off. Lou quickly doused the four headlamps to preserve the battery for ignition purposes, and Earl climbed out on the right front fender with a flashlight. With this crude illuminating system, they continued on across Illinois and into Indiana at a reduced speed until, at about daybreak, they found an open gasoline station. They purchased a new bracket and belt at the station, made some hasty repairs and then continued on to arrive at the Fort Wayne Western Union check point at 9:45 a.m. on August 6.

Advertisement

From Fort Wayne, they continued on across Indiana. across Ohio and then into Pittsburgh where they picked up their first prearranged police car escort. Shortly after picking up the escort, the police car careened around a downtown streetcar on the wrong side of the streetcar. Earl, who was now driving, felt that it would be dangerous — if not suicidal — to follow the police car around the streetcar: as a result, they never saw the police car again.

After picking their way painfully through Pittsburgh, minus their escort, they picked up Route 30 again and now — in the early afternoon hours of August 6 — headed for their fourth service point at Harrisburg. After a hair-raising race across the mountains of western Pennsylvania, they reached Chambersburg. where they picked up Route 11. They raced along Route 11 to Harrisburg, arriving in the early evening of August 6. Here they stopped briefly for servicing, and they plunged on toward New York on Route 22. Some four hours later they arrived at the Eastern terminus of their trip—Tottenville Ferry, New York City.

The time was 1:33 a.m.. August 7, as verified by Western Union. They had made the trip from San Francisco to New York City in 65 hours and 33 minutes – a new coast-to-coast record for any land vehicle.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Their time beat the best combined time of the fastest limited trains between New York and San Francisco by almost 13 hours; it beat the best previous time for an automobile—-established by Cannonball Baker’s Franklin in 1930 over the shorter run from New York to Los Angeles-by three hours and 58 minutes; and it beat the best previous time for an automobile bctween San Francisco and New York by almost 18 hours.

Some indication of the unprecedented speed at which Earl and Lou had made the trip from San Francisco to New York is had by the fact that they were not scheduled to arrive at Tottenville Ferry until the evening of August 7, at which time they were to have been met by Walter Chrysler.

Although Walter Chrysler was in New York as scheduled on August 7, he never saw the PA. After an hour and 12 minute stop at Tottenville Ferry — during which time all four road wheels and two of the spare wheels were changed, new plugs installed, the gap on the points opened somewhat and the tappets and ignition checked — the PA headed westward toward San Francisco.

Advertisement

The drivers were now Lou Miller and Russell Harding, a driver- mechanic employed at Chrysler’s Central Engineering facilities at Highland Park. Earl Pribak, after servicing the car at Tottenville Ferry, stayed on in New York; the next day, he boarded a Boeing tri-motor commercial airliner at Newark Airport bound for North Platte, Nebraska, where he was to rejoin the car.

Lou and Russell’s official departure time from Tottenville Ferry — as verified by Western Union — was 2:45 a.m. on August 7. After speeding across New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania in the early morning darkness, they arrived at their first westbound service point in Harrisburg at about daybreak. From Harrisburg they continued on in the morning hours across the mountains of western Pennsylvania and then into Ohio.

They sped across Ohio and Indiana in the hot afternoon sun and arrived at their first westbound check point in Chicago Heights, Illinois at exactly 8:00 p.m., August 7. A few hours later they arrived at their second service point in Aurora, Illinois. From Aurora they pushed on across Illinois and into Iowa. After an early morning run across Iowa, they rushed across the western border of Iowa and entered Nebraska at daybreak on the 8th of August. Shortly after noon they roared into North Plane, Nebraska.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Here the car was serviced at the third westbound service point-their time of arrival was verified by the local Western Union Office-and Earl Pribak rejoined the PA to replace Russell Harding as relief driver for Lou Miller. Their time of arrival — 12:33 p.m., August 8 — was well ahead of the schedule set up for the return trip. It was so far ahead of schedule, in fact, that Earl Pribak, after flying out to North Platte by commercial airliner, barely had time to catch a few hours sleep before the PA thundered into town.

As Earl and Lou left North Platte headed for Wyoming, they again began to encounter the rough. crushed rock road surface and the detours that had afflicted them during this portion of their Eastward journey; but at least this time the weather was fair. Earl and Lou made the trip across the remainder of Nebraska and most of Wyoming without difficulty.

Shortly after crossing the Continental Divide, Lou noticed that the gasoline gauge was registering near empty. This seemed rather strange since they had only recently refilled the standard tank from the l00-gallon tank. Nevertheless, Earl climbed into the rear seal area to open the control valve to refill the standard tank: but the needle on the gasoline gauge refused to move up from its near empty reading.

Advertisement

A brief investigation of the underside of the vehicle confirmed their suspicions. Something — probably a rock — kicked up from the crushed rock road surface as they sped across the mountains of Wyoming-had punched a sizable hole in the gasoline tank near the bottom of the tank. As a result, the tank would only hold a few gallons. Earl and Lou decided to put off repairing the tank until they reached Rock Springs, Wyoming, now some 65 miles to the West.

A short time-later, as they continued on toward Rock Springs, they noticed a roar developing under the hood. Stopping to investigate, they discovered that the continual pounding of the rough road had cracked the exhaust pipe within the asbestos sleeve surrounding the exhaust pipe adjacent its flanged connection at the front of the engine with the exhaust manifold. The noise was of course no great problem, but the heat released through the cracked exhaust pipe was, since it could — and no doubt would — cause the gasoline in the fuel pump to boil.

After refilling the 100-gallon tank they were again ready to roll.

They resumed their travel toward Rock Springs — now at a much reduced speed to avoid boiling the gasoline — and finally limped into that city in the late evening hours of August 8. Once in the city, they drove directly to the local Button Brothers Plymouth dealership — whose location they had previously verified on their initial trip from Detroit to San Francisco — and after several inquiries managed to locate the home of the dealer who, after being awakened, accompanied them to the dealership to let them in.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Once inside the dealership, Earl quickly removed the entire exhaust pipe, muffler and tailpipe assembly from a shiny new PA sitting on the showroom floor, and installed this system on their dirty, battered PA to replace the damaged system.

He then cut the gasoline line with a hacksaw, punched a hole in the rear floor pan between the front seat and the 100-gallon tank, slipped a 5/16 ID rubber hose over the end of the gasoline line and ran the rubber hose up through the hole in the floor pan and into the opening at the top of the 100 gallon tank. He then secured the hose to the gasoline line with baling wire and tied a monkey wrench to the other end of the hose to hold it in a submerged position within, and near the bottom of the 100-gallon tank. After refilling the 100-gallon tank they were again ready to roll.

They wheeled out of the Rock Springs dealership as midnight of August 8 approached, and sped on toward Salt Lake City over the now paved-but still rough—U.S. 30. They arrived in Salt Lake City at 1:43 a.m. Here, their time of arrival was verified by Western Union and the car was quickly serviced at the fourth and last westbound service point. No attempt was made to repair the gasoline tank since the fuel pump seemed to be drawing gasoline freely from the l00-gallon tank through the improvised rubber hose.

Advertisement

Leaving Salt Lake City, they again picked up Route 40 and headed west in the early morning darkness. Shortly out of Salt Lake City, near Grantsville, Utah, Lou missed a sharp turn in Route 30 — the same sharp turn that Earl had missed on their initial trip from Detroit to San Francisco — and drove into a farmer’s barnyard, the same barnyard that Earl had driven into on the earlier trip. Needless to say, Earl didn’t miss the opportunity to return the kidding that he had earlier received from Lou about his barnyard detour.

After extricating themselves from the barnyard, Earl and Lou continued west, their multiple headlights soon picking up the long straight line of Route 40 as it stretched before them across the Salt Lake Desert. At about 3:30 in the morning they left the Salt Lake Desery and rushed headlong across the western Utah border into Nevada.

A few hours later, as dawn broke on what was 10 be the last day of their trip. they hurtled through Elko, Nevada, and pushed on unrelentingly toward their next and last check point at Reno, Nevada. At 11:40 a.m.. after an uneventful race across the hot rolling terrain of Nevada, they rushed into Reno, Nevada, where their time of arrival was verified by Western Union.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Regaining the highway, they pushed on toward California, crossing the border just after noon. They then climbed the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada mountains, slipped quickly over Donner Pass and began the long run down the eastern slope of the mountain toward San Francisco.

At 5:04 p.m. on August 9 they arrived triumphant at Berkeley Pier in San Francisco. Their time on the western trip, 65 hours and 24 minutes, broke the coast-to-coast record which they had set on the eastbound leg of their trip by 9 minutes. Their total round-trip time of 5 days, 12 hours, and nine minutes, broke the previous round trip record set over the shorter Los Angeles to New York route by 9 and a half hours and shattered the previous San Francisco to New York round trip record by 36 hours.

It is important to keep a proper perspective when viewing the records set by this little PA.

Looking back on this record now, 54 years later, it seems perhaps not so impressive. After all these one-way and/or round-trip records could be — and perhaps many times have been — beaten today by teams of drivers traveling over our new interstate system in modern, high-powered automobiles. But it is important to keep a proper perspective when viewing the records set by this little PA.

Advertisement

The records were set in 1931 in a small, low-powered car over rough, winding, sometimes unimproved two-lane roads and congested city streets. Most significantly, they were records. That is, they represented the fastest that man up to that time had been able to propel a land vehicle of any kind kind across the United States and they decisively shattered records that had recently been set by a professional race driver in a car considerably larger than the PA, almost twice as powerful and several times as expensive.

No matter how you analyze them, the records constitute an everlasting and unequaled tribute to the power, flexibility, smoothness, handling and stamina of the PA model Plymouth.

Lou Miller rested the night of August 9 in San Francisco: the next day he set out in the PA on a 5,000 mile exhibition tour of Eastern cities. Following the exhibition tour, the car was brought back to Chrysler’s Central Engineering facilities in Highland Park, Michigan. From there it was returned to the Plymouth factory where it had been born just a few long months earlier.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The fate of the car is unknown. Perhaps it was stored for a while and then scrapped, perhaps it was deliberately destroyed immediately — or perhaps it is this day rusting away, ignominiously, in an auto graveyard near your home.

This article first appeared in a 1985 issue of The Plymouth Bulletin and was reprinted here with permission. Email us with the subject line “Syndication” if you would like to see your own story syndicated here on Jalopnik.

Graphics credit Jason Torchinsky, Thanks to James Espey for pointing this out.